Video games are big business. According to analytics firm Newzoo the industry was collectively worth $148.8 billion USD globally in 2019. By comparison, the movie industry racked up a paltry $35.3 billion last year. AAA titles with cutting edge graphics are only become more expensive to make, too. Teams of hundreds, even thousands of employees working hard for years to bring us our most anticipated games, adds up to a lot in costs. Yet in theory, the shelf price of a new game seems to hold fast at around $60.

Except, that’s not true at all. Over the decade a whole new lexicon developed in the PC gaming space as an ever-growing industry explored bold new ways of separating us from our money. We learned ”Pre-order bonus,” ”F2P,” ”freemium,” ”microtransaction,” ”battle pass,” and of course the dreaded ”loot box.”

Loot boxes in particular generated a hard backlash that led to some governments finally stepping in to regulate their use towards the end of the decade. Other types of microtransactions are also being looked at by regulators. At the same time the free-to-play Fortnite, the biggest game of the decade, caused a media frenzy by raking in billions through its digital storefront. Google presented Stadia, hyped as a revolutionF2P in the way we consume. Or whatever you call the kind of revolution imposed on a population that wasn’t asking for it.

That’s how the last decade closed out. The new decade has just begun and we’re seeing conflicting visions on how the video game market should operate. Which are the most likely to dominate?

Will the $60 point hold?

Games like Read Dead Redemption 2 costs a huge amount of money to make, consumers don’t want to pay more.

The $60 price point gets thrown around a lot as the benchmark for what a complete video game should cost. But it’s a metric that doesn’t reflect reality in a myriad of ways.

For one thing, the typical AAA title is typically upwards of $90 when you factor in your season pass, day-one DLC, gold edition or whatever the way to get as complete a product as possible is called. On the flip side, I’m sure a lot of us have a backlog of games that we impulse-bought on sale for basically next to nothing. In fact, you’ll usually get a better version of a game for cheaper, so long as you’re willing to wait.

The psychological holding point of $60 remains, seemingly impervious to the effects of inflation. Something else has not risen to meet inflation, namely real wages for the majority of people. Most of us don’t have more spending power than we used to, so $60 still feels like just about the maximum hit to the paycheck most of us can contemplate for a AAA video game.

Which way, AAA?

I say AAA because the world of indie games still generally offers a more straightforward ”buy the whole game and keep it” model at affordable prices. Maybe even too affordable, given the time it takes for an independent creator to make one — and get noticed in the marketplace.

Barring some kind of revolutionary rise in the average person’s earnings, the psychological barrier for AAA titles is likely to hold fast. But the industry, under pressure to report ever-climbing quarterly profits, has found several ways to circumvent it.

I see three main paths this could go. One being additional monetization added on to the individual games. Then there’s going all-in with games as service. Finally, there’s the subscription model; the so-called ‘Netflix of games.’ They all come with their own problems, although I know which I would prefer.

Loot boxes are out, or at least outré…

Everyone hates loot boxes, right? The concept as a whole has become somewhat tainted. Even EA, one of the worst offenders when it comes to the practice, would prefer we use the risible euphemism ‘surprise mechanics’ in reference to its games.

Tim Sweeney criticized loot boxes and “pay-to-win” games at this year’s DICE Summit. During his keynote speech, the Epic Games CEO called for the industry to move away from the trend to a “customer adversarial model.”

“We have to ask ourselves, as an industry, what we want to be when we grow up? Do we want to be like Las Vegas, with slot machines … or do we want to be widely respected as creators of products that customers can trust? I think we will see more and more publishers move away from loot boxes,” Sweeney said.

…but other dark economic models continue

Sweeney’s stance on loot boxes is admirable on its own merits, but it comes from someone who’s comfortably made a fortune squeezing money out of gamers in other ways. Epic Games’ business model isn’t necessarily something we want to follow.

We could look at Fortnite, essentially a digital storefront of goodies marketed to children propped up by a fun multiplayer shooter. Sure, it doesn’t have loot boxes and the battle pass only has cosmetic items. But there is plenty of dark pattern design built into Fortnite‘s in-app purchases and the game itself to keep players compulsively spending. Then there’s the Epic Store, which, instead of developing a better digital storefront than its rival Steam, buys out exclusives instead.

It’s definitely a good thing that loot boxes are becoming a dirty word. But there are other ways to monetize games that are just as ”customer adversarial,” to borrow Sweeney’s phrase.

The problem with piecemeal monetization

There’s a legitimate objection to the use of microtransactions in games, be they loot boxes or not. And it has nothing to do with just how expensive they can get in the long term.

Microtransactions or recurring purchases in games are technically optional. But to be effective they do need to be highly desirable. And the challenge/reward systems of video games can be calibrated to make them as desirable as possible.

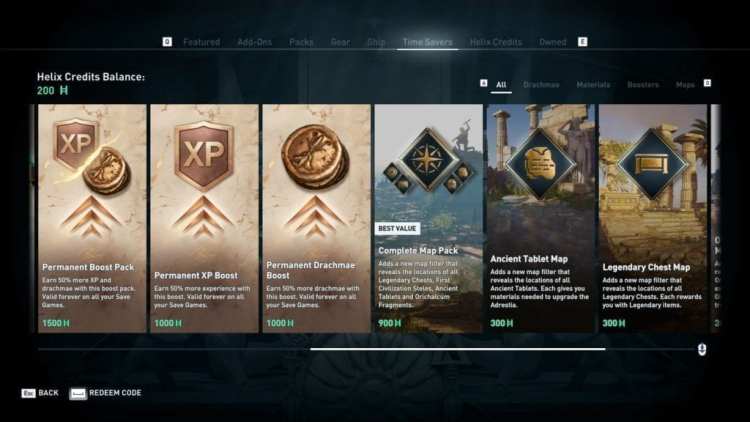

Take, for example, the XP-boost purchase for Assassin’s Creed Odyssey, which actually makes the game more balanced and fun by removing a frustrating grind. Which was a deliberate design choice. Or Fallout 76‘s repair kits, appearing in the game’s ”no pay-to-win” Atom Store as a purchasable item to offset oppressive item degradation.

This kind of monetization incentivizes companies to deliberately place flaws in games so that they can sell the fixes. If you think that video games have any kind of cultural or artistic value at all, this is something that you should be worried about. Imagine if books or movies were designed to be unpleasant or dull in places unless you paid extra. Gambling or no, there’s got to be a way for games to make their money without having to be broken on purpose.

Games as service and the attention economy ceiling

Games as service was a hot industry trend precisely because of the huge amounts of money they could pull in. Fortnite is the best example, being free to play and also raking in billions in revenue. To keep a hold on player’s attention, it updated and changed at an unprecedented rate. This didn’t just give players new things to do, but new things to buy. But how many games like these can really succeed?

It’s an uncomfortable truth of the human condition that our time on Earth is limited. We’re all going to die sometime. We also need to work and sleep, so how we spend our free hours is as important as how we spend our money. In the end, there just isn’t space for many games as service to exist. Any success they get will have to come at the expense of stealing attention away from the others.

Games as service have had their time in the spotlight, but aren’t sustainable for the future. So what about subscribing to a library of games instead of just one?

Subscriptions, streaming, and Stadia: are you not entertained?

The much-anticipated ‘Netflix of games’ is apparently always on the horizon but has yet to materialize. Streaming comes with its own baggage of technical hurdles, but a subscription model is another way for games to get their revenue without increasing the purchase price or relying on dodgy microtransactions.

Stadia’s announcement in 2019 spawned a ton of media buzz. There was excitement for an innovative and convenient new product. Skepticism about how well it could really work, given most people’s less-than-stellar internet connection. And fear, because it looked to herald another nail in the coffin of game ownership, where you wouldn’t even have the files on your machine!

But it’s 2020 now and we’re still waiting for the revolution. Google is notorious for only half-heartedly supporting new initiatives in the long term. The Google graveyard has become quite crowded. Stadia already appears to be losing momentum, with Google seemingly reluctant to take an active role in promoting the games on the service.

Stadia isn’t really a Netflix-style subscription service. You still buy the games to play on it, even with streaming-only access. It does offer a library of free games over time for Pro tier subscribers, but its main appeal is convenience, not the payment plan. Without powerful hardware, Stadia can be appealing. For anyone who has a decent machine but prefers a subscription for the actual games, Stadia ain’t it.

Game Pass: the best of both worlds?

Xbox Game Pass, which came to PC in 2019, is a more straightforward subscription service without Stadia’s streaming woes. The $5 monthly fee accesses a library of over 100 games. The games can be bought outright at a discount. You download and install the games on your own PC. Mods are possible. You can even play offline so long as you log in every 30 days to verify your subscription.

Even a few hundred titles isn’t a huge choice given the variety of games out there. But paying $60 a year to access AAA games with the option to buy outright is a much better deal for the consumer than shelling out north of a hundred dollars for each ‘complete’ title. Paying for full games via subscription also removes the annoyances of having to bypass deliberate flaws with microtransactions. Hopefully, it would also take the pressure off studios to implement such things in the first place.

Just like with games as service, subscription services will have their own turf wars fighting over our free time. We can see that in the video space with Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Disney+, Hulu, etc. But I’d rather see that kind of competition than more games chopped up for microtransactions, or more beloved story-based franchises like Fallout be turned into games as service product.

If the AAA industry is serious about moving away from the customer adversarial model and preserving the integrity of the games, then offering a viable subscription service will be the way forward in 2020. Let’s also hope that as consumers, we can continue to hold the industry accountable for the next time the ‘adversarial’ elements creep in.